When people say a service dog “ignores distractions,” they don’t mean the dog never notices anything. They mean the dog stays neutral and steady—able to keep working even when real life gets noisy, tempting, or unpredictable. A well-trained service dog can move through public spaces without being pulled off-task by food smells, other animals, sudden sounds, people trying to say hello, or busy environments like shopping centers and transit stations.

That reliability isn’t magic, and it usually isn’t just a dog being “naturally perfect.” It’s built through a training plan that layers skills over time: strong focus basics, thoughtful exposure to distractions, clear cues, and lots of repetition in many locations. The goal is a dog that can notice something interesting, then choose the trained response—stay in position, check in, follow a cue, and remain ready to perform specific tasks when needed.

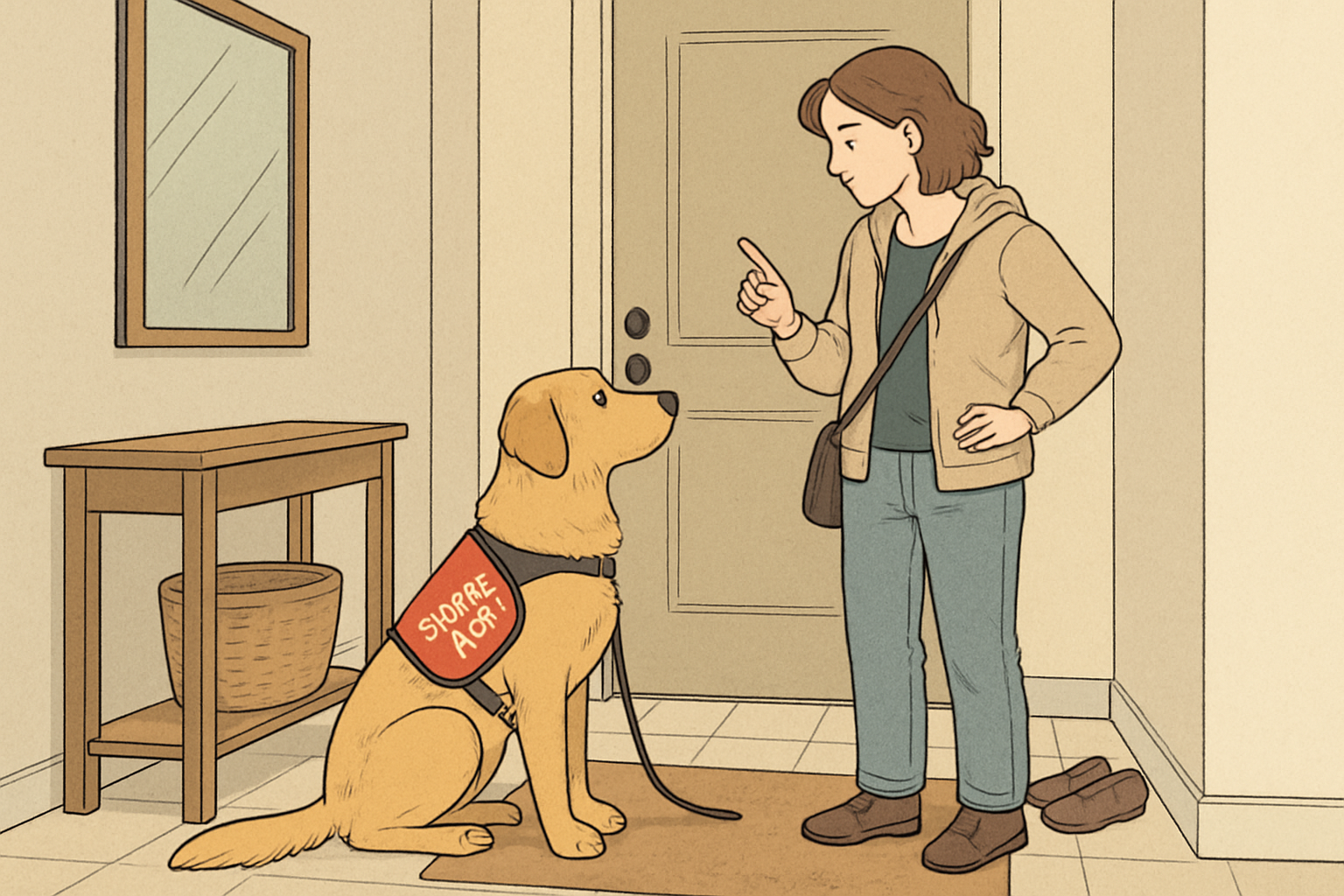

Distraction-resistance starts where success is easy: at home, in a quiet yard, or in calm, familiar spaces. Early on, trainers set the dog up to win. That means choosing a place where the dog can respond quickly to their name, follow simple cues, and settle without struggling against the environment.

A practical way to think about it is to control three knobs: distance (how close the distraction is), duration (how long the dog needs to hold it together), and intensity (how exciting or scary the distraction is). If any one of those gets too high too soon, the dog may “check out,” fixate, or get overwhelmed. If you keep those knobs manageable, the dog can practice the right choice repeatedly—and repetition is what creates reliability.

Once a dog can focus in low-distraction settings, trainers begin gradual exposure to the real world: shopping carts rolling, kids running, doors whooshing open, coffee grinders, elevators chiming, dogs passing by, and unexpected movement. The key word is gradual. Instead of throwing the dog into the hardest version of an environment, trainers introduce distractions at a level the dog can handle calmly, then slowly increase realism and proximity over multiple sessions.

This approach helps the dog learn a powerful lesson: “That stuff happens, and I’m still okay.” Over time, the dog’s nervous system stops treating common triggers like emergencies or invitations to party. They become background noise—noticed, but not acted on.

Many trainers follow a stepwise plan: begin where the dog can succeed, raise difficulty in small increments, and increase reward support around distractions to keep the dog engaged. This systematic progression is widely recommended in distraction training plans, including strategies described by clicker training educators source.

In early distraction training, the environment often has “bigger rewards” than the handler: food smells, movement, friendly strangers, or other animals. Positive reinforcement helps balance the scales. Trainers temporarily pay the dog well for choosing focus, calm body language, and correct positioning around distractions—then gradually reduce (fade) rewards as the behavior becomes fluent.

Reward timing matters as much as reward choice. In distraction-heavy moments, it’s most helpful to reward when the dog makes a good decision: choosing to look back at you, staying in heel, relaxing their body, or ignoring something tempting on the ground. Over time, the dog learns that the safest, most rewarding choice in public is staying connected to their handler.

“ "When distractions went up, we didn’t get stricter—we got clearer and more generous with rewards. That’s what helped my dog choose me consistently." – Service dog handler”

Dogs do better when they know what to do, not just what not to do. Service dog training often includes clear “focus cues” and alternative behaviors that give the dog a job when something distracting appears. Instead of staring, pulling, or drifting away mentally, the dog is prompted into a trained pattern: heel position, hand target, eye contact, or an automatic check-in.

These skills are also useful because they’re portable. If the environment changes suddenly—someone drops a bag, a child runs by, a cart squeaks—your dog has a familiar behavior to fall back on.

And if something is simply too hard in the moment, management is allowed. Creating more distance, moving briskly past a distraction, or using a visual barrier (like stepping behind a display or turning down a quieter aisle) isn’t “failing.” It’s smart handling that protects the dog’s learning and keeps outings smooth.

Sometimes distraction training isn’t just about obedience—it’s about emotions. A dog might be overly excited by people, worried about loud noises, or intensely interested in other dogs. Engage/Disengage (often taught as “Look at That”) is a simple game that changes how the dog feels about a distraction by making calm observation and reorientation to the handler the rewarding pattern.

Instead of punishing the dog for noticing something, you teach: “You can look, and then you come back to me.” Over time, the distraction becomes less powerful because it reliably predicts a calm reward and a clear next step.

Most service dog teams follow a gradual public-access progression. This helps the dog generalize skills across environments, not just perform in one familiar place. Sessions are typically short, upbeat, and structured—ending before the dog becomes tired or frustrated.

Many teams also rehearse “simulated public” drills. These are set up to be realistic but controlled—like a friend dropping a piece of food, someone approaching to chat, a sudden (not terrifying) noise, or a cart passing by. Because the trainer controls intensity, the dog practices correct choices without being surprised into a big reaction.

Even well-trained dogs can find certain “hotspots” harder than open space. These are moments where the environment changes quickly or feels crowded, and distractions tend to pile up. Good teams plan for these situations instead of being caught off guard.

A helpful habit is to “pay before the hard part.” If you know your dog tends to struggle at automatic doors or in narrow aisles, deliver a reward and a clear cue before you enter that zone. That proactive support often prevents the mistake from happening in the first place.

A service dog’s focus is a team effort. Small handler habits—especially consistency and clarity—can make distractions feel far less tempting. Dogs thrive when cues mean the same thing every time, reinforcement is predictable during learning phases, and training sessions end on a success.

“ "When I started treating distractions like a training opportunity instead of a problem, my dog relaxed. My job became setting the difficulty level, not proving something." – Service dog trainer”

Even with good preparation, dogs can have moments: staring hard at another dog, pulling toward dropped food, or jumping at a sudden noise. The most effective response is calm and practical—focus on lowering difficulty and rebuilding success rather than “pushing through” a big reaction.

If your dog is having repeated big reactions, consider working with a qualified trainer who uses humane, reward-based methods. A customized plan can help identify what’s too hard right now and how to safely build back up.

A big part of “ignoring distractions” is avoiding unnecessary interruptions—especially in places where people are curious, ask questions, or approach closely. Many handlers find it helpful to carry clear, professional identification and simple educational materials so interactions stay brief and respectful. When expectations are clearer, teams can stay focused on calm movement and task readiness instead of getting pulled into repeated conversations.

Service animal registration, IDs, and related materials are optional tools that many teams use for organization and everyday clarity. Having consistent documentation can also be convenient for recordkeeping and for smoothing routine public interactions.

Some handlers choose a customizable service dog ID card for clear everyday identification so they can present information quickly and keep attention where it belongs—on the dog’s working behavior and the handler’s needs.

Travel adds a whole new layer of distractions: rolling luggage, loudspeaker announcements, security lines, hotel lobbies, unfamiliar elevators, and long days that can tire any team out. The strongest travel teams usually practice calm behaviors in “new but manageable” environments before the trip—so the dog learns that novelty still follows the same rules.

For trip planning and expectations, many handlers like a guide to traveling with a service dog, especially when mapping out lodging, rest stops, and routines.

Some teams also prefer keeping travel paperwork and identifiers in one place with a travel-ready service dog registration package for on-the-go convenience, which can make logistics feel more organized during busy travel days.

Because attention is a powerful distraction. A service dog may be actively monitoring their handler, maintaining position, or preparing to perform a trained task. Even friendly talk can pull the dog’s focus away at the wrong moment.

Give the team space when possible, pass calmly without rushing, and avoid reaching toward the dog. If you need to get by, a simple “Excuse me” directed to the handler (not the dog) helps everyone move smoothly.

Food on the ground is one of the most tempting distractions for dogs. Service dogs are trained to ignore it so they can stay safe, avoid scavenging, and remain ready to work—especially in busy places like grocery stores and food courts.

Yes. Laws, policies, and practical expectations can vary depending on where you are. When in doubt, respectful communication and giving a working team space go a long way.

For handlers who want an easy way to share helpful information quickly and respectfully, some carry ADA law handout cards for quick, respectful communication to reduce misunderstandings and keep outings calm and efficient.