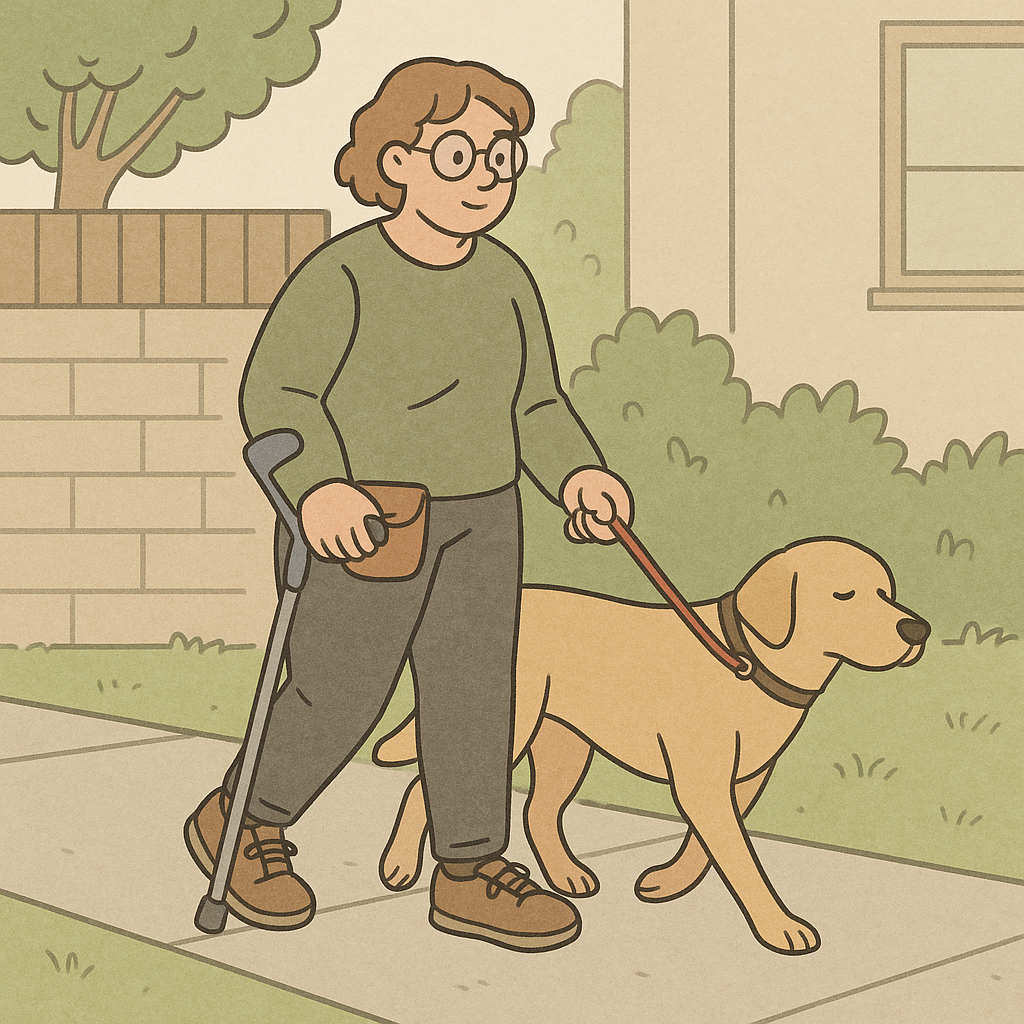

Yes—if you have a disability, you are allowed to train your own service dog under federal law.

Under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), a “service dog” is defined by what the dog is trained to do: the dog must be individually trained to perform specific work or tasks that help mitigate (reduce the impact of) the handler’s disability. The ADA does not require that a service dog come from a professional program, a specific trainer, or a particular organization. In other words, owner-training is legal—and many people successfully do it.

That said, legal permission and real-world readiness aren’t the same thing. Public access comes with practical standards: the dog must be under control, housebroken, and able to behave appropriately around the public. This article breaks down what federal rules actually say, what businesses can and can’t ask you, how public access works, why “service dogs in training” are treated differently, and where state or local rules can add extra layers.

The ADA definition is specific: a service animal is a dog that is individually trained to do work or perform tasks for a person with a disability. The tasks must be directly related to the person’s disability.

This is where many misunderstandings start—especially online. People often use “service animal” as a general term for any animal that provides comfort or emotional support. But under the ADA, the difference is task-training.

Here’s how the most common categories compare:

Service dog (ADA): A dog trained to perform specific disability-related tasks. Public access rights apply when the dog meets behavior standards.

Emotional support animal (ESA): Provides comfort by presence, but is not trained to perform disability-related tasks under the ADA definition. ESAs are not service animals under the ADA.

Therapy animal: Typically visits hospitals, schools, or community settings to provide comfort to others. Therapy animals are not service animals under the ADA.

Examples of tasks that may qualify (depending on the handler’s disability and training): guiding a person who is blind, alerting a person who is deaf, retrieving dropped items, pulling a wheelchair, interrupting harmful behaviors, reminding a handler to take medication, or alerting to certain medical changes.

“ "The moment my dog reliably learned to retrieve items I can’t safely bend for, daily life became less painful—and a lot more independent." – Service dog handler”

One of the biggest myths about service dogs is that you must carry “official certification” or show a registry card to enter public places. Under the ADA, there is no required certification, registration, ID card, vest, or set of training papers.

What can a business ask? In places open to the public (restaurants, stores, hotels, etc.), staff are generally limited to two questions when it isn’t obvious what the dog does:

1) Is the dog a service animal required because of a disability?

2) What work or task has the dog been trained to perform?

They cannot require you to disclose your diagnosis, explain your medical history, demonstrate the task on the spot, or provide documents as a condition of entry. The goal is to balance access for disabled handlers with reasonable, limited verification.

If you want to read the exact guidance and common examples straight from the ADA, you can review the official FAQ here: source.

No. Under the ADA, businesses generally can’t require paperwork, a vest, or an ID card. They may ask the two permitted questions when the need isn’t obvious.

It’s optional. Many handlers choose an ID card or certificate as a convenient communication tool to reduce confusion in day-to-day situations, but it isn’t legally required for ADA public access.

Even though the ADA does not require paperwork, it does expect a certain standard of behavior in public. Public access is not “automatic” just because a dog is intended to become a service dog. The dog needs to be trained and reliable enough to be in public spaces safely.

In practical terms, a service dog in public must be:

Under control: Usually on a leash, harness, or tether—unless those devices interfere with the dog’s work or the handler’s disability prevents their use. In that case, the dog must still be controlled by voice, signal, or other effective means.

Housebroken: Accidents in public spaces are a legitimate problem and can be grounds for removal.

Trained to perform disability-related tasks: The task training is what makes the dog a service dog under the ADA definition.

Also important: A business can ask that a dog be removed if the dog is out of control and the handler does not take effective action, or if the dog is not housebroken. That can be true even if the dog is a legitimate service dog. When removal is necessary, the business should still offer the person the chance to get goods or services without the animal where possible.

“ "Public access isn’t about perfection—it’s about control, safety, and predictability. A service dog should look boring in public." – Experienced service dog trainer”

Owner-training is legal—but it’s important to understand a common limit: the ADA does not grant public access rights to service dogs in training.

That means that even if you are disabled and actively training your future service dog, federal ADA rules don’t automatically allow you to bring that dog into non-pet-friendly places while the dog is still learning.

However, some state or local laws do allow service dogs in training to access certain public places, and some of those laws also extend access to trainers (not only disabled handlers). Because this varies widely, it’s smart to check the rules:

Where you live

Where you’re visiting

Whether the law distinguishes between “in training” and “fully trained”

If your dog is still inconsistent, it’s often easier (and kinder to the dog) to focus training in pet-friendly environments until reliability is strong.

Federal ADA rules are the baseline for public access—but state and local laws can add practical requirements that apply to dogs generally and can offer additional benefits for service dog handlers.

Common local requirements that may still apply to service dogs include:

Vaccination requirements (like rabies)

Licensing requirements

Leash laws (unless a leash interferes with task work and the dog is otherwise controlled)

Some cities or counties also offer perks, like reduced licensing fees for service dogs. To receive those local benefits, you may be asked to complete a form or provide documentation such as an affidavit. That kind of paperwork is about local administration (like a fee waiver)—it does not change the ADA rule that you don’t need “registration” to access public places with a trained service dog.

It’s also worth noting that many jurisdictions take false claims seriously. Misrepresenting a pet as a service dog can lead to penalties and creates real problems for disabled handlers who rely on legitimate, trained dogs.

No. Local paperwork may be required to receive a local benefit (like reduced licensing fees), but it doesn’t create a federal requirement for public access.

In many areas, yes—general public health and licensing rules can still apply. Check your city/county requirements.

Flying with a service dog is governed by Department of Transportation (DOT) rules under the Air Carrier Access Act (ACAA), not the ADA. That matters because airlines can have specific procedures, forms, and behavior expectations.

Owner-trained service dogs are allowed for air travel, but the dog still must be task-trained to assist with a disability and must be able to behave safely in crowded, high-stress environments like airports, security lines, and tight seating areas.

To prepare, it helps to review a complete guide on traveling with a service dog and plan ahead so you’re not scrambling at check-in.

The law may allow owner-training, but the bigger question is: is your dog a good candidate for service work?

Service work is demanding. The dog needs the temperament to stay neutral around strangers, food, carts, sudden noises, and unexpected movement. The dog also needs the ability to learn complex behaviors and perform them reliably—even when the environment changes.

A great service dog prospect is typically:

Stable and calm in new environments

People-neutral and dog-neutral (polite, not desperate to greet, not reactive)

Motivated to work with the handler

Physically healthy and structurally sound for the tasks needed

Reliability matters because service tasks often happen when you need them most—during pain spikes, panic symptoms, mobility challenges, or medical events. A useful benchmark is consistency: can the dog perform trained behaviors correctly in multiple public settings and recover quickly from distractions?

The ADA does not limit service dogs by breed. In real life, suitability depends on the individual dog’s temperament, health, and ability to reliably perform needed tasks.

Friendly is a great start, but service work requires focus. Many teams build reliability through structured training, gradual exposure, and consistent practice in pet-friendly places before attempting more challenging environments.

Owner-training tends to go smoother when you follow a progression. The goal is to build a dog who is safe, confident, and predictable in public before you rely on them for high-stakes access.

A practical high-level order looks like this:

1) Foundation skills: Engagement with you, name response, leash manners, sit/down/stand, recall, leave-it, and a strong settle. These are the building blocks for everything else.

2) Socialization and environmental exposure: Carefully introduce surfaces, sounds, people, carts, doors, elevators, and different environments in a controlled way. The goal is calm neutrality, not frantic friendliness.

3) Public-access behaviors (in pet-friendly places first): Loose-leash walking, ignoring food and strangers, riding elevators calmly, waiting politely, tucking under tables, and being able to settle for longer periods.

4) Task training: Teach the disability-related tasks you need (retrieval, alerts, interruption behaviors, guiding to exits, etc.). Then practice until the tasks are reliable.

5) Proofing: Practice the same behaviors in new locations, with more distractions, at different times of day. This is where reliability is built.

A key safety point: avoid bringing a dog into non-pet-friendly public spaces until the dog is fully trained and dependable. Many owner-trainers make faster progress by practicing in pet-friendly stores and gradually increasing difficulty.

Even if you’re committed to training yourself, working with a qualified trainer for evaluations and troubleshooting can save time and prevent bad habits from becoming long-term problems.

Many conflicts around service dogs aren’t about the law—they’re about confusion, inconsistent training, or tense conversations at the door. A calm plan can prevent a small misunderstanding from turning into a stressful scene.

Common pitfalls include:

Staff asking for “papers” because they believe certification is required

Handlers being pressured to disclose their disability

Confusion between ESAs and service dogs

A dog being disruptive (barking, pulling, sniffing shelves, approaching people) and the team being asked to leave

Assuming a vest or ID is required (or assuming it guarantees access)

When you’re questioned, it can help to answer the two permitted questions clearly and briefly, without oversharing.

Simple scripts you can use:

If asked “Is that a service dog?”

“Yes. This is my service dog required because of a disability.”

If asked “What does it do?”

“He’s trained to perform tasks that assist with my disability.” (Then name one or two task examples, such as “retrieves items” or “alerts me to a medical issue.”)

It can also help to carry a short ADA summary to de-escalate. Not as “proof,” but as a way to keep the interaction respectful and efficient—especially if the staff member is simply misinformed.

“ "I’ve found that staying calm and answering the two questions confidently prevents most issues. It’s usually not personal—just a lack of training on the business side." – Owner-trainer”

A vest isn’t required under the ADA. What matters is that the dog is task-trained for a disability and meets behavior standards (under control and housebroken).

If the dog is disruptive or out of control, the business can require removal. The best approach is to exit calmly, regroup, and continue training in a setting that matches your dog’s current skill level.

Because service dog rules are widely misunderstood, many handlers choose optional tools that make everyday interactions smoother—especially in places where staff turnover is high and policies get repeated incorrectly.

It’s important to be clear: IDs, certificates, and online “registrations” are not required by the ADA and do not create legal rights by themselves. They can, however, function as practical communication aids. For example, a simple handout that summarizes the two permitted questions and basic standards can help staff quickly understand the rules without a long debate.

If you like the idea of a simple, non-confrontational way to educate politely in the moment, consider keeping ADA law handout cards in your bag or car. The best use is straightforward: as a helpful reference, not as “proof” or a claim of government certification.

If you choose to use an ID card or certificate, stick to accurate language and avoid implying that it’s federally issued or required. Clear communication protects you, protects businesses, and supports the credibility of legitimate service dog teams.

Owner-training can be empowering, but it isn’t the best match for everyone—and that’s okay. The time commitment, consistency requirements, and the “washout rate” (dogs who ultimately aren’t suited for the job) can be higher than people expect.

If you need support, alternatives include:

Working with an organization program: Some groups place fully trained service dogs, though waitlists can be long.

Hybrid programs: Some trainers or organizations help train your personal dog (when available), combining owner effort with professional structure.

Private professional guidance: Hiring a qualified trainer to coach your plan, evaluate temperament, and troubleshoot can be a cost-effective way to stay on track without handing everything off.

This isn’t about “needing” an advanced or official path. It’s about matching the training approach to your disability needs, your dog’s temperament, and the level of reliability required. For complex or high-stakes tasks, expert oversight can add safety and confidence.

Federal law is clear: you can train your own service dog. Under the ADA, a service dog is defined by individualized task-training that helps mitigate a disability—not by where the dog came from, who trained it, or whether you have a certificate.

At the same time, public access depends on real-world standards. The dog must be under control, housebroken, and able to behave appropriately in public. Service dogs in training don’t automatically have federal access rights, so it’s important to check state and local rules before training in non-pet-friendly spaces. And if you plan to fly, remember that airlines follow separate ACAA/DOT requirements.

If you’re considering owner-training, prioritize safety, reliability, and respectful access. A well-trained, task-skilled dog can change daily life—especially when the training is approached thoughtfully, honestly, and with the public standards in mind.