Assistance dogs do impressive work in busy, unpredictable places—stores, sidewalks, offices, medical appointments, airports, and more. But even well-trained dogs have limits. Stress is the body’s way of saying “this is a lot,” and when it builds, it can affect a dog’s comfort, focus, and willingness to keep working.

For a working team, stress isn’t just about behavior—it’s about reliability and safety. A dog who is overwhelmed may miss cues, respond slowly, or struggle to complete tasks that normally look easy. In some cases, a stressed dog may try to escape a situation, shut down, or become overly vigilant. None of this means the dog is “bad” or “disobedient.” It means the dog needs support.

Catching subtle signs early helps you prevent a small moment of discomfort from turning into an overload. Over time, consistently responding to stress signals builds trust: your dog learns that you will listen, advocate, and make the environment feel safe. That trust is part of what keeps assistance work stable for the long term.

Stress signals are easiest to spot when you know what “normal” looks like for your dog. Every dog has a baseline: their typical posture, breathing pattern, facial expression, and energy level when they feel safe and comfortable. Some dogs naturally pant more, some carry their tail lower, and some are naturally more watchful—even when relaxed.

To learn your dog’s baseline, observe them in low-pressure settings: at home after a walk, during a quiet training session, or while resting on a familiar patio. Take note of how their eyes look, how their ears sit, and what their mouth does when they’re content. Then, when you’re in a more challenging environment, you can notice the small changes sooner.

Many stress signals show up first in a dog’s face and posture. These cues can be subtle—especially in dogs who are trying hard to keep working. Watching your dog’s whole body (not just the tail) gives you the clearest picture.

Common facial stress cues include lip licking, yawning when the dog isn’t tired, quick tongue flicks, a slight head turn away, ears pinned back, “whale eye” (showing the whites of the eyes), and dilated pupils. You may also notice a tight mouth, a closed mouth after previously panting, or an intense stare that looks more like worry than focus.

Body-language cues can include a tucked tail, trembling, shifting weight back, crouching, paw lifting, increased shedding, or increased panting that doesn’t match the temperature or activity. Some dogs slow down and “stick” to the handler’s leg; others speed up and appear restless.

Not always. Dogs yawn when tired, waking up, or settling down. It becomes more meaningful when it appears alongside other signals (lip licking, pinned ears, avoidance) or shows up repeatedly in a challenging situation.

Panting can be normal for temperature regulation. It can also signal stress when it’s sudden, intense, paired with tense posture, or happens in cool conditions without exercise.

Stress doesn’t only show up in body language. Many assistance dogs show overload through changes in behavior, responsiveness, or vocalization. These shifts can be especially noticeable after a challenging outing—when the dog is back home and finally “lets go.”

You might see pacing, circling, sudden clinginess, withdrawal, or a dog who tries to hide behind you or under a table. Some dogs go unusually quiet and still; others become vocal with whining, barking, or grumbling. Stress can also impact appetite (refusing treats that are normally motivating), digestion, and house habits—occasionally leading to indoor accidents if the dog is overwhelmed or their routine is disrupted.

For working teams, one of the most practical red flags is a change in task performance: tuning out known cues, slower responses, sloppy positioning, or needing repeated prompts. If your dog is normally steady and suddenly struggles, it’s worth considering whether the environment, duration, or pace of the day has become too much.

“ "The first sign for my dog isn’t barking—it’s that he stops taking treats and starts scanning. That’s my cue to slow down and give him a break before he’s over his limit." – Assistance dog handler”

Assistance dogs work in environments that are full of challenges. Some triggers are obvious, like loud noises. Others are quieter but constant, like repeated interruptions from strangers or long periods of sustained focus without a true break.

Common triggers include crowds, tight spaces (narrow aisles, elevators, waiting rooms), unpredictable environments (kids running, carts clattering, sudden announcements), and frequent attempts by the public to talk to, reach for, or distract the dog. Even positive attention can be stressful when it’s nonstop.

Physical discomfort can also raise stress quickly. Illness, sore muscles, itchy gear, paws irritated by hot pavement, or gastrointestinal upset can make normal tasks feel hard. Another major factor is duration: long workdays, back-to-back errands, or skipping decompression breaks can stack stress until the dog can’t recover fast enough.

When you notice stress signals, the goal is not to “push through.” The goal is to respond early and kindly so your dog can stay safe, comfortable, and capable of working with you. Stress is easiest to manage when you treat it like a sliding scale—low, moderate, and high—based on clusters of signals and how quickly your dog can recover.

Many service dogs show recognizable clusters of stress signals, and early intervention—creating distance, doing a quick reset, or ending the session—can prevent escalation and reduce the risk of unreliable performance. For a helpful overview of how clusters of stress signs can appear in working dogs, see this source.

In public, one practical stress reducer is minimizing conflict and repeated conversations. Having ADA law handout cards for quick, calm communication in public can help you set boundaries and move on without prolonged interaction—often lowering pressure on both you and your dog.

A reset is a short, low-pressure moment that helps your dog’s nervous system settle. It’s not about drilling obedience or proving the dog can handle more. It’s about helping your dog feel safe enough to think again.

Often the best reset is simply moving: step out of the main flow of foot traffic, turn down a quieter aisle, or find a corner where your dog can breathe without being stared at. Then use easy, high-success cues your dog enjoys—like sit, touch, or a short hand target—to re-center attention. Keep it calm and brief, and watch whether your dog’s body softens.

“ "The reset isn’t training harder—it’s giving my dog a chance to feel steady again. If she relaxes, we continue. If she doesn’t, we’re done." – Assistance dog handler”

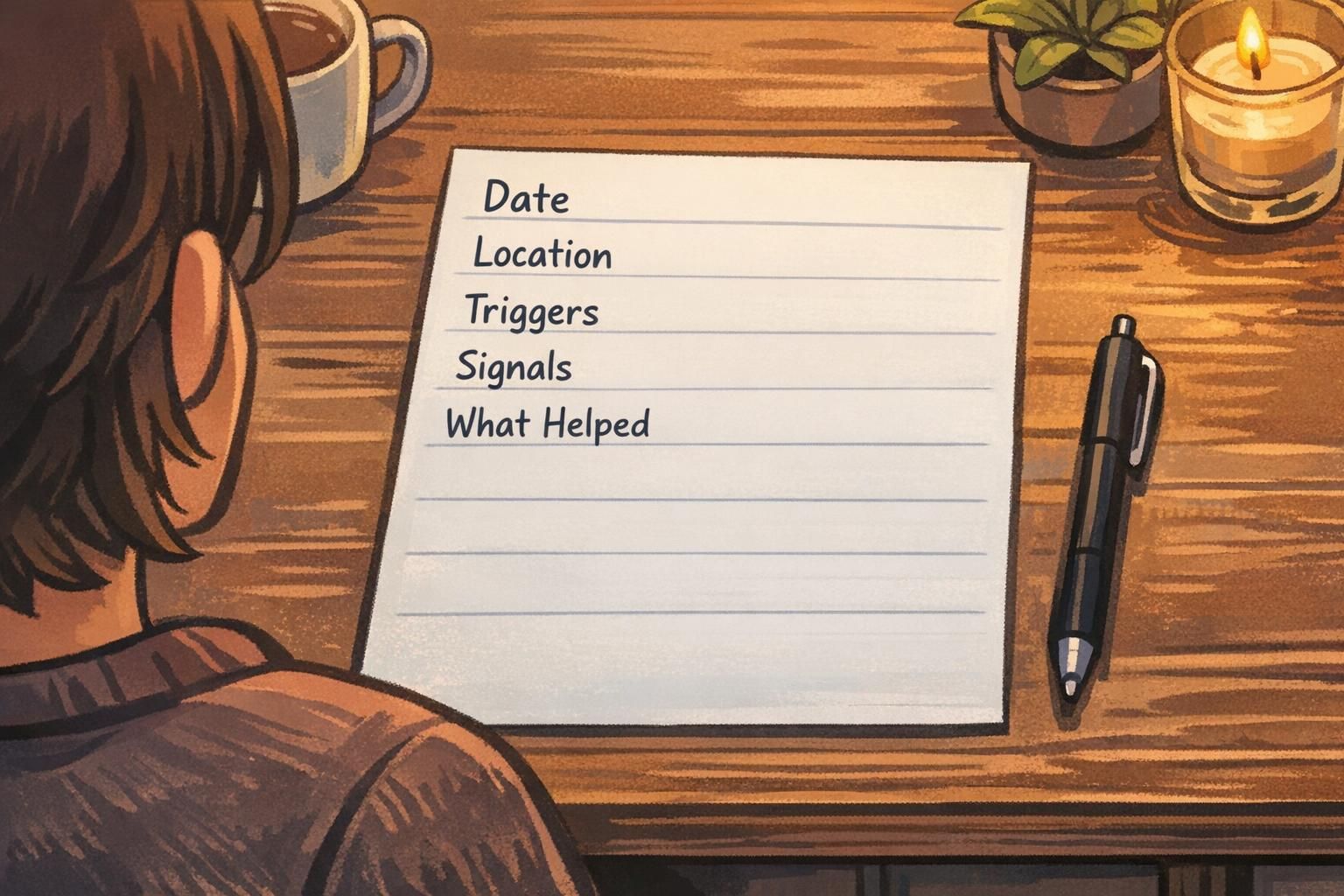

One of the fastest ways to improve your team’s day-to-day comfort is to track patterns. A simple stress log helps you notice what your dog finds difficult, what helps them recover, and how long they can work comfortably before stress starts stacking.

Your log doesn’t need to be complicated. Consistency matters more than detail. Over time, you may notice patterns like: certain stores are harder than others, afternoons are tougher than mornings, or long lines are the main tipping point. With that information, you can adjust your routine—shorter trips, more breaks, different routes, or planned decompression time after intense outings.

Stress signals are normal, but frequent overload is a sign to pause and reassess. Getting support early is not a setback—it’s how many teams stay successful long-term. A skilled trainer or veterinary behavior professional can help you identify triggers, improve coping skills, and rule out discomfort that might be making work harder.

Consider reaching out for extra help if you notice frequent high-stress clusters, persistent avoidance of working environments, regression in house training, or sudden behavior changes that don’t match your dog’s history. It’s also wise to consult a veterinarian if stress appears alongside changes in appetite, sleep, mobility, or gastrointestinal issues.

Many assistance dogs experience stress not because the environment is inherently scary, but because the social pressure is constant. Repeated approaches—“Can I pet?” “Is that a real service dog?” “What’s wrong with you?”—can create friction that wears down even confident teams.

Clear, consistent boundaries help your dog predict what will happen: no petting, controlled greetings only when you choose, and predictable breaks. When your dog doesn’t have to manage random interactions, it’s easier for them to stay focused and relaxed.

Some teams also find it helpful to use professional, consistent identification to reduce repeated questions and keep interactions brief. Having a starter registration package for clear everyday identification can support smoother day-to-day outings by making your working role easier to communicate at a glance.

Travel can be a perfect storm for stress: long lines, crowded terminals, rolling luggage, loud announcements, unfamiliar floors, schedule changes, and less control over personal space. Even dogs who do well on routine outings may show more stress signals during travel days simply because everything is more intense and less predictable.

Planning breaks is one of the most effective ways to prevent stress spikes. Build in buffer time so you’re not rushing. Identify quieter corners in advance, and schedule potty breaks and water breaks like they’re non-negotiable parts of the trip. If your dog shows early stress signals, respond early—small decompression moments can prevent a full overload later.

For more ideas, see travel planning tips for teams working on the go.

If you like having everything organized for travel, a travel registration package designed for smoother trips can be a convenient way to keep key materials consistent and easy to access while you focus on your dog’s comfort and your own pace.