In everyday conversation, people often use “service dog” as a catch-all term for any dog that helps someone feel better or functions as a companion. In practice, though, different types of support animals are treated differently in public settings. That distinction matters because it affects where a dog can go, what questions a business can ask, and what behavior is expected during public access.

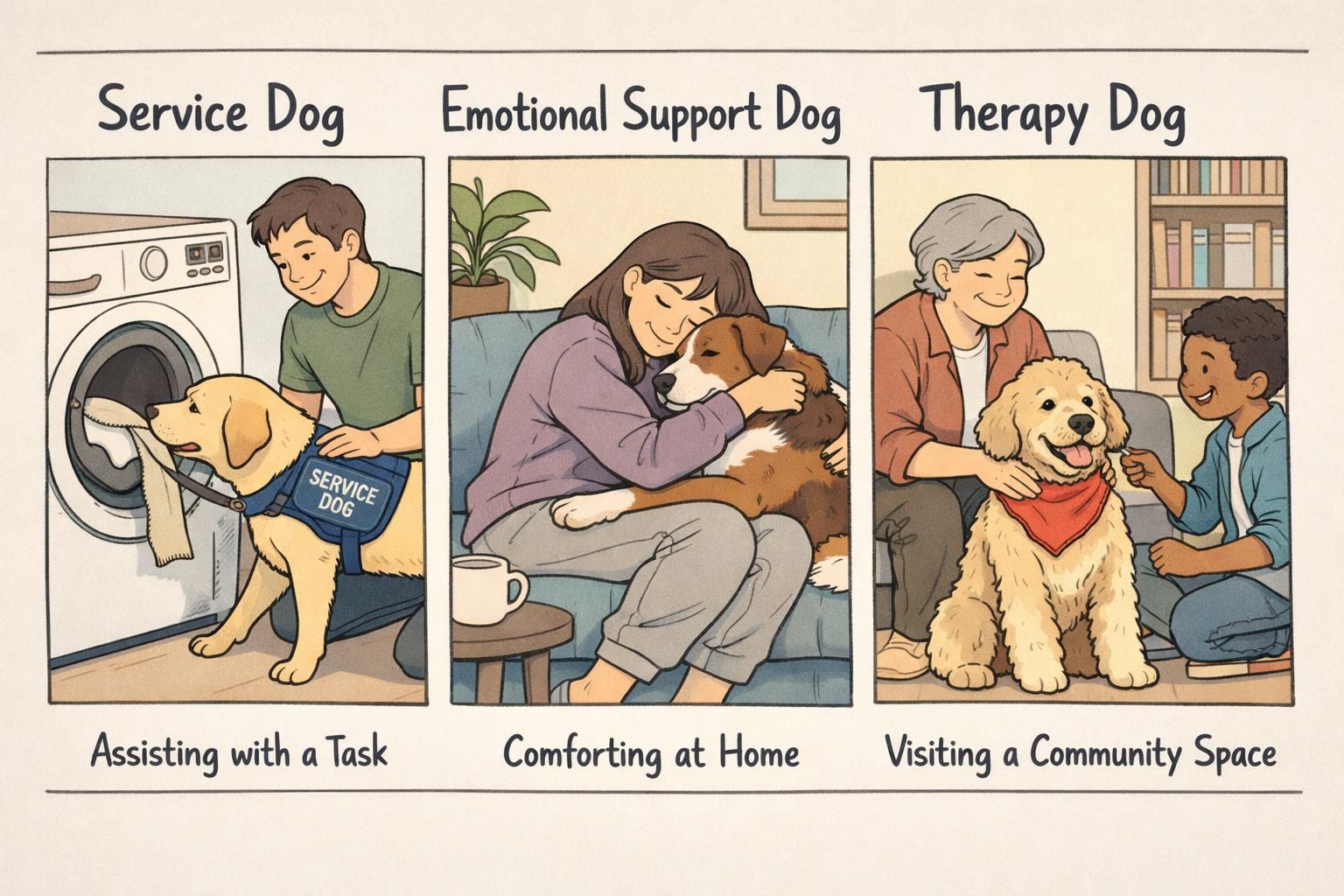

A service dog is generally associated with trained, disability-related help in public life—like guiding, alerting, or assisting with daily tasks. Emotional support animals (ESAs) are typically valued for their presence and comfort, often in home or housing contexts. Therapy dogs usually work with a handler to provide comfort to other people (for example, visiting a school, hospital, or community program) rather than assisting one individual handler with a disability.

Under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), a service animal is a dog that is individually trained to do work or perform tasks for a person with a disability. The “task” part is the key: it’s not about a dog being well-loved, calming, or helpful in a general way—it’s about trained, reliable actions that directly relate to the person’s disability.

Examples can include guiding a person with low vision, alerting to a sound for someone who is deaf or hard of hearing, retrieving dropped items, providing mobility support, interrupting or responding to a psychiatric episode with a trained behavior, or reminding a handler to take medication. The ADA framework also explains how service animal rules apply across many public places and what public-facing staff are allowed to ask in the moment. For the ADA’s core definitions and guidance, see this source.

Many excellent dogs provide real comfort and support—without meeting the specific service dog standard used in public-access settings. If you’re unsure where your dog fits, it helps to look at the most common reasons a dog may not qualify as a service dog in day-to-day public life.

If your dog is already doing disability-related tasks or you’re actively training toward them, it can help to reduce confusion with clear, consistent identification. Many handlers choose a clear, ADA-friendly service dog ID as an everyday tool—especially in busy public spaces where quick clarity makes interactions smoother.

Even when a dog does qualify as a service dog, public access depends on behavior, safety, and hygiene. In real life, businesses and public spaces can ask a handler to remove a dog that is out of control, disruptive, or not housebroken. This isn’t about judging someone’s disability—it’s about ensuring the environment remains safe and functional for everyone.

This is one reason training “public manners” matters just as much as task training. A dog can be talented at a disability-related task at home, but if the dog can’t remain calm and controlled around strangers, food, carts, or tight aisles, the team may not be ready for certain public settings yet.

Public misunderstandings often come down to questions—what staff are allowed to ask, and how a handler can respond without feeling put on the spot. In ADA-covered public settings, staff are generally limited to two questions when it isn’t obvious what service the dog provides.

In contrast, staff should not demand medical details, ask for a diagnosis, require documentation as a condition of entry, or insist on a task demonstration in the moment. Many handlers find it helpful to practice a calm, one-sentence answer that focuses on trained tasks rather than personal health information.

Keep it short and task-focused: “He’s trained to retrieve items and provide deep pressure therapy during an episode,” or “She alerts to medical changes and guides me to a safe place.”

In public-access settings, you can usually answer the permitted questions without discussing your diagnosis. A task-based answer is typically enough.

If you prefer a simple, respectful way to reduce friction, many handlers carry wallet-sized ADA law handout cards for smoother conversations. They can be especially useful during high-stress moments when you want to communicate clearly without debating.

People often search for “service dog requirements” hoping for one checklist that applies everywhere. While laws define what a service dog is, day-to-day success usually comes down to practical readiness: the dog’s trained task performance, the dog’s public manners, and the handler’s ability to maintain control.

Training can be done in many ways. Some teams work with professional trainers; others owner-train; many use a mix. What matters most is that the dog can do the disability-related work reliably and behave safely and calmly in public environments.

“ "The best public-access training goal isn’t perfection—it’s predictability. A reliable, unobtrusive dog makes life easier for the handler and for everyone sharing the space."”

Most people who struggle with the service dog label aren’t trying to cause problems—they’re trying to get through daily life with a dog that genuinely helps them. The issue is that when a dog is presented as a service dog without trained disability-related tasks, or when the dog’s public behavior is disruptive, it can create conflicts that spill over onto other legitimate teams.

Poorly prepared dogs in public can lead to increased scrutiny, tense interactions at entrances, and safety concerns for the public and for other working teams. The goal isn’t to shame anyone—it’s to encourage an honest match between your dog’s current training level and the environments you’re bringing them into.

In daily life, the biggest challenges often aren’t legal—they’re practical: check-ins, quick questions at the door, new staff who aren’t sure what to ask, or travel and housing situations where you want your information organized. Registration, IDs, and certificates can be helpful tools for creating clarity and consistency, especially when you’re interacting with people who don’t understand service and support animal categories.

Many handlers appreciate having a consistent profile they can reference, a unique registration number, and a clear ID card that communicates the dog’s working role at a glance. These tools can also help reduce day-to-day friction by making your information easy to confirm and easy to present when you want to be proactive.

If you’re looking for a simple, all-in-one way to organize your information, consider a starter registration package for everyday identification.

One reason people feel confused is that “the rules” can change depending on where you are and what you’re doing. Public access in many everyday locations falls under ADA-style concepts, while housing and travel can involve different policies, different paperwork expectations, and different timelines.

A calm planning mindset helps: confirm what category your dog falls into for that situation, review the current requirements for the airline, landlord, or program, and keep your dog’s training and behavior top of mind. If you want a helpful overview for timing and prep, this guide can help with planning ahead when traveling with a service dog.

For handlers who want a more organized travel setup, a travel-focused service dog registration package can be a convenient way to keep key information and materials together for check-ins and on-the-go conversations.

If you’re trying to decide what label fits your dog right now, a quick self-check can bring clarity. Think of this as a practical snapshot of today—not a judgment of your progress. Many excellent teams grow into public access over time.

You can start by identifying a specific need tied to your disability and working toward a trained behavior that meets that need (often with step-by-step practice). At the same time, build calm public manners so your dog can handle real-world environments.

Choose training-friendly environments, keep sessions short and successful, and use clear communication tools when appropriate. Many handlers also use consistent identification materials to help others understand the dog’s role without long conversations.