The words “service dog,” “emotional support animal,” and “therapy dog” often get used interchangeably—but they mean very different things in training, purpose, and where the animal is allowed to go.

An assistance dog (often called a service dog) is a dog trained to perform specific tasks that mitigate a person’s disability. These tasks aren’t just helpful tricks—they’re reliable, disability-related skills that improve independence, access, and safety. This task-focused role is what sets service dogs apart from other support animals (see source).

An emotional support animal (ESA) provides comfort through presence and companionship. ESAs can be extremely beneficial, but they are not required to be task-trained.

A therapy dog is typically a friendly, steady dog that visits facilities (like schools, hospitals, or senior living communities) to provide comfort to many people. Therapy dogs do important work, but they don’t have general public access rights as a working partner for one disabled handler.

A dog can certainly provide comfort and also perform trained service tasks. The key difference is whether the dog is trained to reliably perform disability-mitigating tasks—if so, it fits the service dog category.

Training can come from many paths, including owner-training with help from a qualified trainer. What matters most is that the dog can reliably perform disability-related tasks and behave appropriately in public.

Most service dog work fits into four broad categories: guide, mobility, medical alert/response, and psychiatric service. These categories are useful because they describe the kind of problems the dog helps solve—navigation, movement, medical safety, or mental health stability.

In real life, many teams don’t fit neatly into one box. A handler might need a dog that both retrieves items and performs deep pressure therapy, or a dog that guides and also alerts to blood sugar changes. The best plans start with the handler’s real daily challenges, then build a task list that supports safety, access, and participation—whether that’s getting through a grocery store, making it through a work shift, or feeling stable enough to ride public transportation.

Guide dogs help blind or low-vision handlers move safely through public spaces. Working in a harness with a handle, a guide dog provides directional support while the handler remains responsible for decisions like where to go and when to cross. The dog’s job is to make that route safer—helping avoid obstacles, stopping at curbs and stairs, and guiding around hazards like sidewalk clutter.

One of the most impressive guide skills is “intelligent disobedience.” That means the dog may refuse a command if following it would be unsafe—like stepping into traffic, moving forward when a curb isn’t actually clear, or proceeding into a blocked area. This safety-first mindset is a hallmark of guide work and a major reason guide dogs are so life-changing for the people who partner with them.

“ "My dog doesn’t just ‘walk with me’—he actively keeps me out of danger. The first time he refused to move forward at a crosswalk, I realized what intelligent disobedience really means." – Service dog handler”

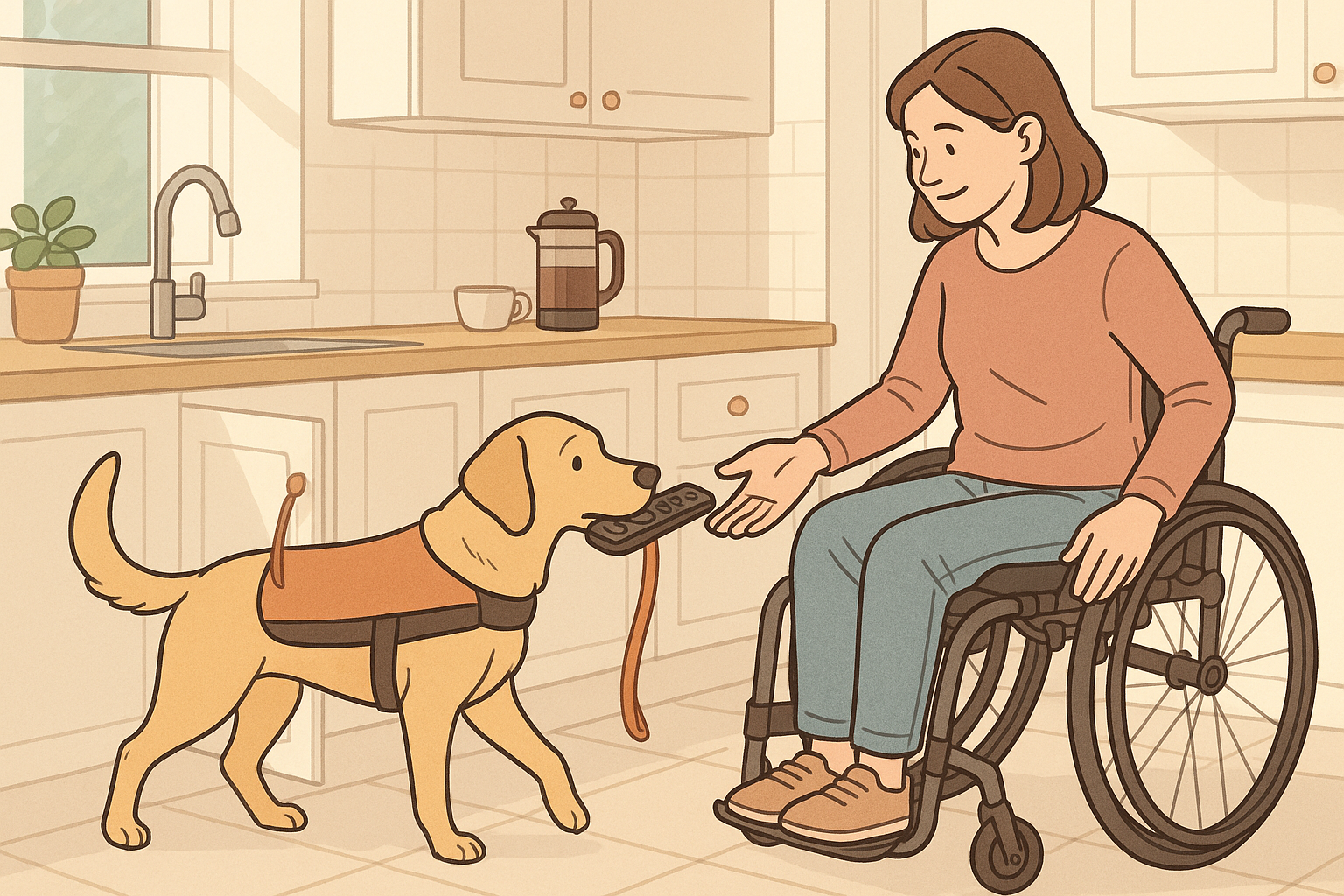

Mobility assistance dogs support people with physical disabilities by reducing strain, preventing falls, and making daily routines more manageable. These dogs may partner with handlers who have spinal cord injuries, cerebral palsy, arthritis, muscular dystrophy, or other conditions that affect strength, balance, coordination, or stamina.

Many mobility tasks look simple from the outside—but the impact can be enormous. Picking up dropped items can prevent painful bending or unsafe transfers. Tugging open a door can mean the difference between independence and needing to call for help. Turning lights on or off can make nighttime routines safer.

Some mobility dogs also learn more physically demanding skills such as pulling a wheelchair short distances or assisting with transfers. Balance and bracing tasks deserve special care: the dog must be the right size and structure, properly conditioned, and equipped with an appropriate harness setup. The goal is always safety for both handler and dog.

No. Bracing and balance support should only be trained and used when it’s safe for the dog’s body and the handler’s needs, with appropriate size, conditioning, and equipment.

Retrieval is often a strong foundation task because it reduces strain and can be trained in many environments before adding more complex public-access routines.

Medical service dogs generally fall into two working styles: alert and response.

An alert dog is trained to notice changes that happen before a medical episode—often through scent, subtle body cues, or early behavioral signs. A response dog is trained to help once an episode has started, assisting with safety and recovery. Many dogs do both, depending on the handler’s needs.

Common examples include diabetic alert work for blood sugar changes, seizure response tasks such as fetching medication or a phone, getting another person for help, applying deep pressure to support recovery, or guiding the handler to a safer place. Some dogs are also trained for allergen detection, helping the handler avoid exposure.

You may also hear reports of alerts related to conditions like POTS or Addison’s disease. Because individuals vary and not every dog is capable of consistent pre-alerting, it’s best to view these as possible for some teams rather than guaranteed. The gold standard is always reliability: the dog’s trained behaviors should be clear, consistent, and practical in real-world situations.

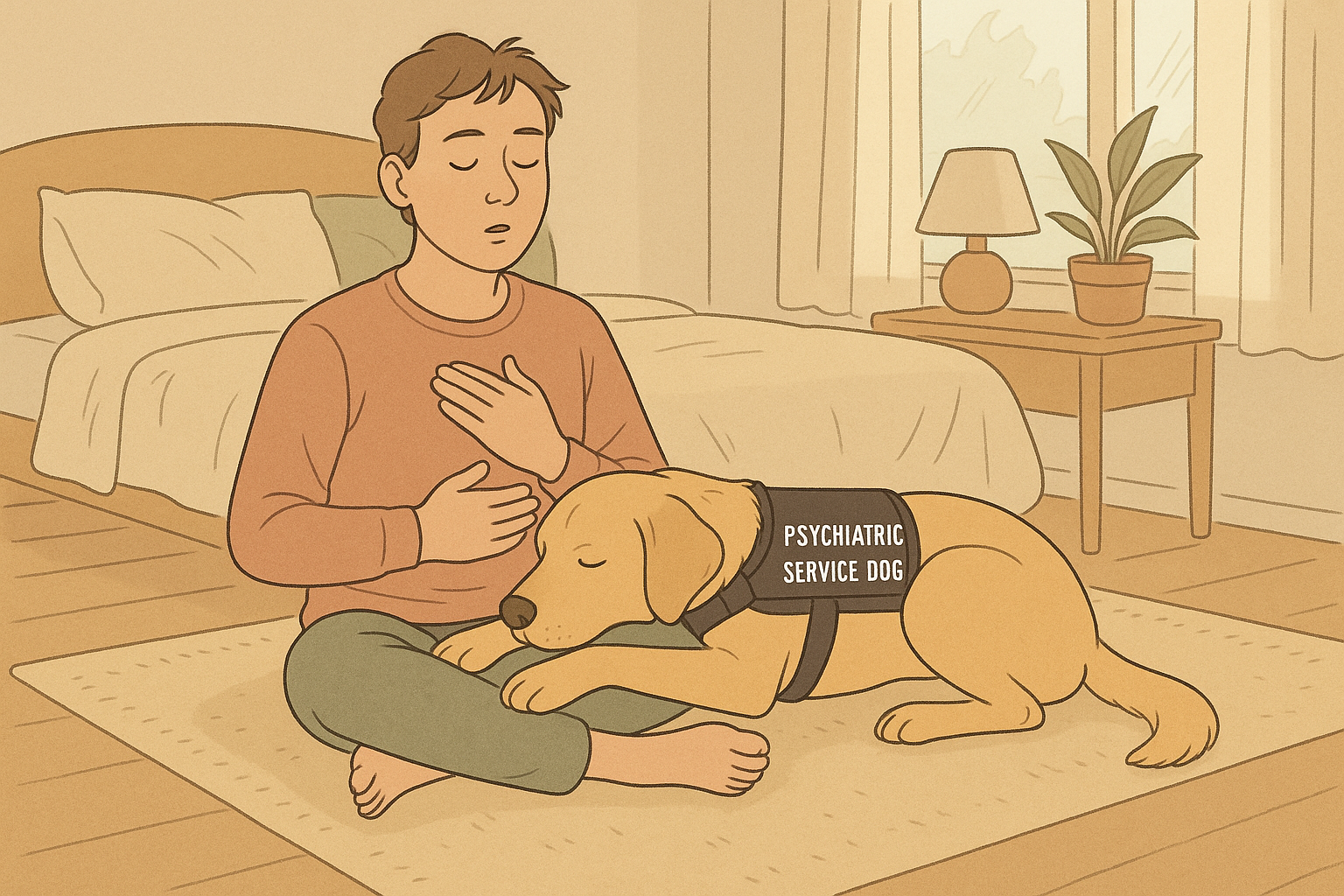

Psychiatric service dogs are not “just comfort animals.” They are trained to perform specific tasks that help a handler manage a psychiatric disability and function more safely in daily life.

For PTSD, anxiety disorders, panic disorder, and related conditions, tasks often focus on interrupting escalating symptoms, grounding the handler in the present, and creating a practical sense of safety in environments that would otherwise be overwhelming.

Examples include deep pressure therapy (DPT) during panic, “blocking” or “covering” to create a buffer in crowds, waking a handler from nightmares, performing a room sweep to reduce hypervigilance, or turning on lights to reduce fear and disorientation. These tasks are concrete, trained behaviors designed to reduce the impact of disabling symptoms—not simply emotional comfort.

“ "When my breathing starts to spiral, my dog’s trained pressure cue is like a reset button. It gives me something physical to focus on so I can follow my coping plan." – Psychiatric service dog handler”

Many handlers don’t experience challenges in only one category. A person might have a mobility disability and PTSD, or be low-vision while also managing blood sugar swings. In those cases, a single service dog may be trained to perform tasks across multiple roles.

Dual-purpose teams can be incredibly effective, but they require thoughtful planning. Safety-critical skills should come first—things like stable public behavior, reliable recall, and any tasks that prevent injury. From there, teams can add additional tasks in a structured way so the dog stays confident and consistent.

The goal isn’t to teach “every cool task.” It’s to build a small, reliable set of behaviors that genuinely improves day-to-day life and holds up in real-world conditions like noise, crowds, travel, and distractions.

It’s helpful to set realistic expectations: a dependable assistance dog is the result of consistent training, careful socialization, and a temperament that can handle the public world. Not every friendly dog enjoys busy stores, sudden noises, or constant novelty—and that’s okay. Service work requires social stability, confidence, and a willingness to focus.

Training can take a long time, especially when a dog is learning to generalize skills to many environments. Some programs invest years into selecting, raising, and training dogs, which is one reason fully trained dogs can be expensive. At the same time, reputable organizations may place dogs at low or no cost for qualified applicants, depending on funding and mission.

No matter the path, the practical standard is reliability: the dog should perform trained tasks consistently and behave appropriately around the public. Ethical sourcing matters too—healthy breeding practices, humane training methods, and a clear commitment to the dog’s welfare should always come first.

It varies widely by dog, tasks, and training plan. Many teams spend substantial time building public behavior, task reliability, and confidence across different environments.

It prioritizes the dog’s welfare, uses humane methods, and focuses on steady, repeatable skills rather than fear, intimidation, or shortcuts.

Daily public access is a skill set—for both handler and dog. The best outings tend to be the calmest ones: simple routines, clear expectations, and a focus on the dog’s working behavior.

For handlers, it helps to prepare short, polite scripts for common moments—like someone trying to pet the dog, or staff who aren’t sure about access rules. Staying steady and matter-of-fact can prevent small interactions from turning into stressful conflicts.

For the public, the most respectful thing to do is treat the team like any other person going about their day. Don’t distract the dog, don’t pet without asking, and avoid making kissy noises or calling the dog to you. Even friendly interruptions can pull a working dog off task at a critical moment.

Some handlers find it helpful to carry quick, clear information they can hand out when needed, such as ADA law handout cards.

Confidence outside the home comes from planning, repetition, and taking care of the dog’s needs while you handle your own. Before errands or travel days, many teams pack a few essentials and keep routines predictable: where the dog rests, when water breaks happen, and how bathroom breaks are handled.

New environments can be tiring—even for experienced dogs—so it helps to build in decompression time. A short calm walk, a quiet “settle” break, or returning to the car for a minute can keep the dog’s stress low and performance high.

If you’re learning the ins and outs of airports, hotels, and longer trips, resources like traveling with a service dog can help you think through the details. Some handlers also like having a simple set of travel-facing materials in one place, such as a service dog travel package, to make day-to-day advocacy feel more organized.

Choosing the right type of assistance dog starts with your real life—not with a label. Begin by identifying disability-related challenges that limit safety, access, or daily functioning. Then look for patterns: when do you struggle most, and what kind of help would change the outcome?

A practical approach is to turn those moments into tasks. For example: “I drop items and can’t safely bend” becomes “retrieve dropped items.” “I become disoriented during panic” becomes “interrupt panic and guide me to a safe spot” or “deep pressure therapy.” “I miss early signs of low blood sugar” becomes “trained alert behavior.”

Once you have a task list, match the tasks to a category—guide, mobility, medical, psychiatric—or a combination. From there, it’s wise to consult medical professionals and reputable trainers or programs to confirm that the tasks are appropriate and safe for your needs and for the dog. The best match is the one that reliably supports your day-to-day independence while keeping the dog healthy, confident, and comfortable in the role.

That’s common. Focus on the specific tasks that would help you most. Many teams are multi-task, and task needs matter more than a single label.

Prioritize safety and daily functioning: tasks that prevent injury, help you access essential places, or reduce the impact of episodes in a practical way.